…in an urban village?

This was the topic of the first Paper Crane Tea 2014.03.09. I’m posting the link because my VPN isn’t fast enough to tunnel video over or under the great firewall. Will upload next time I’m in Hong Kong. Sigh.

…in an urban village?

This was the topic of the first Paper Crane Tea 2014.03.09. I’m posting the link because my VPN isn’t fast enough to tunnel video over or under the great firewall. Will upload next time I’m in Hong Kong. Sigh.

Unfortunately, more often than not modernization leaves us with street names instead of actual landscape features.

Shenzhen public landscaping, for example, has been defined by its enthusiasm for inaccessible green space that adorn its roads. Throughout the city, there are lovely swathes of topiary and grass that pedestrians (and even birds) can’t actually access except in passing. In part to rectify this problem, but also in response to the city’s white collar residents, a vast network of bike trails have been installed throughout the city. Moreover, these trails have been mapped and the public encouraged to walk and ride through the cities green belts.

Here’s the moment of ecological dissonance: at the same time that functionaries are being encouraged to bike on the weekend, plans have been announced to reclaim 39.7 sq kilometers of Dapeng Bay. The corporate culprit is China Oil, which intends to use the reclaimed land for extracting South China Sea oil reserves. And yes, these plans are moving forward despite the fact that Dapeng New District is an environmental conservation district.

So pictures of the Nanhai (literally “South Ocean”) Road, below and a link to an article about the land reclamation project, here.

What’s in a name, indeed.

This past week I have been in Wuhan, the political, economic, cultural, transportation a land educational center of China. Like it’s US American sister cities Pittsburgh and St Louis, once upon an early industrial time, Wuhan thrived and sparkled and offered developmental opportunities that paradoxically challenged and reinforced coastal hegemonies, in New York and Shanghai, respectively.

Wuhan also faces the challenge of restructuring its heavy industrial economy, even as young people migrate to coastal cities for more contemporary opportunities. In Shenzhen I know many Wuhan people involved in the City’s creative industries. In point of fact, Wuhan has more college students than any other city on the planet, which is to say the city grooms talent that leaves for elsewhere, carrying dreams and solid heartland values in suitcases that fuel coastal growth.

I moseyed around two of Wuhan’s historic areas, one famous the other not so. Hankou boasts colonial architecture and a formerly robust mercantile history. Tanhualin in Wuchang was long ago the site of a Buddhist temple and later the location of Christian missions, including churches, schools and a hospital. Impressions of ongoing historic convergence, below.

Impressions of a walk along Fuhua South Road. This is one of the oldest areas in the city. Of note, the street is busy and vibrant and runs parallel to Shennan Road, which is wide and long and filled with vehicular traffic, but few pedestrians.

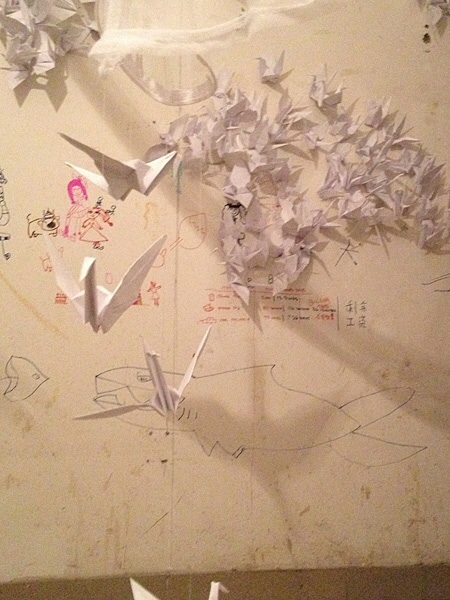

Today, we had the first tea at 302. The conversation ranged from why urban villages through the muddled terms–city in village, farmer laborer–of contemporary urbanization to the ubiquity of urban villages throughout China. We also laughed. A lot. Impressions below.

Yesterday, the Shenzhen Government online portal announced that Baishizhou is on the list of areas designated for urban renewal.

The plan to renew “the five Shahe villages” was submitted by the Shenzhen Baishizhou Investment Company Ltd. It calls for razing 459,000 square meters of built area. The area has been zoned for residential and commerce, with at least 135,857 square meters of public space.

Baishizhou is one of 18 projects announced. All plans take place at the street level, and all target communities and/or early industrial areas. All emphasize the planned public area, but do not mention plans for evicted residents or scheduled construction.

Of note, the urban renewal announcements were tucked away in the Bureau of Land, but the announcement of Shenzhen’s plans for its first village preservation project, Shayu (沙鱼涌古村保护项目) made the front page.

The article title is “A Good Shenzhen Doctor was Beaten, He Refused to Prescribe Unnecessary Medicine or Vitamin Drip”. The article reminds Shenzhen readers that although it is common to abuse doctors in neidi, it has not been common in Shenzhen. Moreover, as the article points out, often the beatings occur even when the Doctor is doing her job.

The use of the word “good doctor” and the assumption that sometimes doctors deserve to be beaten for (corruption, expensive medicine, fill in the angry blank) underscores the tense relationships between patients and doctors in China generally, but also Shenzhen, our low number of reported conflicts notwithstanding. As in the US and elsewhere, in contemporary China lay people assume that role of medical care is to return patients to perfect health, immediately. More distressingly when this result cannot be obtained, patients and their families assume that their ongoing dis-ease is deliberate and that the Doctor is withholding care in order to receive a bribe. Hence, the beatings.

In my experience, it is important to know one’s doctor because some Chinese doctors do put a price tag on treatment. Sometimes they do prescribe expensive, unnecessary treatments. Like US doctors they often preen and show off their knowledge. But more often than not, like their patients, Chinese doctors are caught in an ugly web of mistrust and impossible desires. Doctors cannot heal everyone all the time, and they are shackled by all sorts or regulations and administrative cost. Moreover, as in the US, hospitals and clinics do turn away those who cannot pay but won’t die from lack of treatment. Also as in the US, patients want the best modern medicine without paying for it and often those who can afford medical care oppose government subsidies for those who cannot.

But there’s the rub: except for the very rich few people can afford out-of-pocket treatments and so they only go in when very sick or for antibiotics and other instant (preferably cheap) cures. There is little conversation about general prevention, and less about two unavoidable facts–our collective lifestyle makes us sick (cancer and diabetes, for example) and despite all our technology, we will get sick, age, and die. Hopefully, with grace and dignity.

The hope for graceful lives and dignified deaths changes the conversation about whither medical care. As a society, we need investigate what it would mean to provide equal and gracious access to care. We need to think seriously about what constitutes a dignified death. And we need to take responsibility for the contamination that our dependence on petrochemicals and nuclear power has introduced into shared environments because not only humans are suffering from our hubris.

Marc Augé famously suggested that airports are non-places because they are too transient to have an identity. Other non-places include highways, hotel rooms, and waiting rooms. Augé used the idea of the non-place to describe the dislocations and standardizations that characterize super modernity.

Of note, our shopping mall cities, Shenzhen for example, offer few concrete (literally!) objects that have particular and recognizably distinct identities. At the MixC in Luohu and coastal City in Nanshan, for example, we see the same mix of chain stores, domestic and international arranged in a space that is more luxurious than the Rockaway mall of my teenage years, but in essence no different. The comparison, chez Shenzhen is with an imagined countryside and the urbanized villages. In other words, supermodern shopping malls are a place holder in the search for something better, but not interesting in and of themselves.

Today, I am in Hong Kong international airport and have noticed a few replicas of preserved buildings. Such is the anonymity of the super modern city that we even become nostalgic for colonial architecture — smaller and distinct from the airport, which dwarfs these toylike memories of a quaint accessible, familiar and endearing city that never was.

The day before yesterday I participated in a Biennale forum on high density living. I thought high density living referred to number of people living in so much space. Rumor has it, for example, that there are roughly 19.5 million people living in Shenzhen — a mere 4 million over the official unofficial population count (read generally accepted and quoted). Shenzhen has an official area of 1,952 square kilometers, which would make the SEZ’s estimated actual population density to be around 10,000 people per square kilometer. The population density of people with hukou would be significantly less dense, around 1,300 people per square kilometer, but no one believes that figure. On the recently updated Chinese Wikipedia the population density is given as being 5,201 per square kilometer.

Population density can be appropriated to give us a sense of forms of social inequality. Baishizhou, for example, is located in Shahe Street Office, which has an area of approximately 25 square kilometers. The estimated population is around 260,000, giving us an average population density of 10,400 people per square kilometer, which is close to the guesstimated municipal average above. However, when we account for Baishizhou, we see an interesting realignment.

Baishizhou occupies an area of .6 square kilometers (the rest of the area’s original holdings has already been annexed by the state). It has a guesstimated population of 140,000 people. This means that Baishizhou has a population density of 23,333 people per square kilometer, while the rest of Shahe, which includes Overseas Chinese Town and Mangrove Bay estates has a population density of 4,898 people per square kilometer. So Baishizhou has a population density which is over twice the municipal average and OCT and Mangrove Bay areas have a population density that is less than half the city average.

I was wrong in thinking that population density is the only way to operationalize unequal access to space. In archi-parlance (that’s a personal neologism for “how architects and urban planners talk about the world and stuff they’re building), there are two more definitions of density that they’re interested in measuring– floor area ratio (FAR) and dwelling unit density (DU). And if you’re wondering do they further abstract these descriptions of the built environment by using acronyms, the answer is a resounding yes! The density atlas provides an illustrated explanation of terms. Below, I try to work through what these terms might tell us about the spatialization of unequal access to space through and within Shenzhen’s urbanized villages.

FAR density refers to how much building occupies the space. And it’s three-dimensional. So floor area ratio means the total area on all floors of all buildings on a certain plot. Thus, a FAR of 2 would indicate that the total floor area of a building is two times the gross area of the plot on which it is constructed, as in a multi-story building. So, a FAR of 10 would be ten stories, if the base was consistent (as in a box). (And yes, I’m grappling to get my mind around this kind of abstraction so I think in simple terms, or word problems if you will.)

In order to calculate DU density, you posit so many square meters per person. A 100 square meter building with a FAR of 6 would have 600 square meters. If we then posit 20 square meters per person, our 600 square meter building could shelter 30 people. In other words, if we were to take standard person to space ratio used by many Shenzhen urban planners, then 30 people could comfortably live in one handshake building.

But clearly that’s a calculation for one, single purpose building. Once we start allocating space for functions, we need to make value judgments. How much space for business? For women’s restrooms in public spaces? For sleeping? In other words, to allocate spaces within the built environment we need to make decisions that will reveal and confirm our sense of what is the good life and how we will share that life and it’s material components. To return to our hypothetical 6-story handshake building, if we give the first floor to business and then build subdivide a floor into (3.5 X 6) 21 sq meter efficiencies (still above the magic 20), three on one side of the hallway and one on the other, we would get four rooms. However, if we further subdivide those rooms, we could get eight even smaller rooms (leaving space for hallway and stairs).

In practice, design is not that simple. But the numbers do begin to operationalize inequality in terms that resonate the ethical discourse modern education has equipped us with. For example, the layout of Handshake 302 shows a living space of (4.335 X 3.06) = 13.2651 square meters. There is a small cooking space and toilet which also allows for standing baths. Our neighbors live in similar sized rooms, and share the space and rent among two or three roommates. This suggests that the actual DU in a Baishizhou handshake efficiency can be as low as 4.4 square meters per person. At 850 per month, wear talking a rental cost of 64.1 yuan per meter.

In contrast, it costs 18,600 to rent a condo at neighboring Zhongxin Mangrove Bay, for example. The flat has four bedrooms, two living rooms, and three bathrooms that take up a total of 265 square meters, or slightly less than half a handshake building. It is a family home, so let’s guesstimate a pair of grandparents, a set of parents and one kid, totaling five people. Each of them enjoys 53 square meters of living space. Each square meter has a rental cost of approximately 70 yuan, which is not that much higher than Baishizhou.

Admittedly, one can tell many stories with statistics, but the square meter story of Baishizhou and its neighbors is one of gross inequality. Mangrove Bay residents can occupy anywhere from 15 to roughly 18 times the space of Baishizhou renters, and pay about 22 times the cost for that privilege. At this scale, one can begin to imagine what razing Baishizhou means in terms of affordable housing on the one hand and potential profit on the other. Point du jour, however, is that there is no “standard” square meter per person ratio, just expanding levels of inequality.

So, some stats du jour that should give us pause to reflect on the values we are constructing into the built environment.

Useful maps of Shenzhen administrative divisions online here. Includes municipal and district maps.