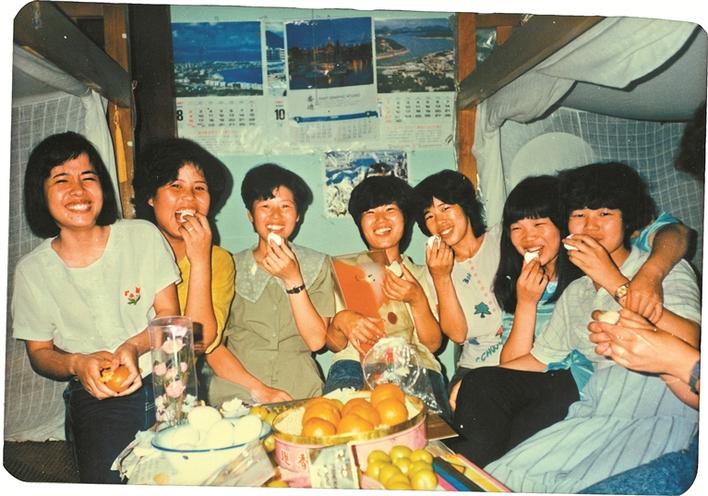

May 13, 2024 I attended a TEDish event that was jointly sponsored by Hougongfang (厚工坊) and Fenghuang Media Shenzhen (凤凰网深圳). If you drink baijiu, then you’ve probably heard of Hougongfang, a high-end brand of Moutai from Wuyeshen (五叶神), which is based in Guangdong, but brews in Maotai. if you follow Shen Kong media, then you’ve clicked a Fenghuang post or two. The company is primarily state-owned and based in Shenzhen and Hong Kong, offering Mandarin and Cantonese language programming. It is registered in the Cayman Islands. The event theme was “厚浪” which is a homophone for 后浪 (waves or next wave) and also neatly reminds us of Moutai’s (Maotai’s) historical significance, which was consolidated during the Chinese civil war and especially pronounced (chez Shenzhen) during the 1990s and naughties, when deals were sealed with toasts and no one went home sober.

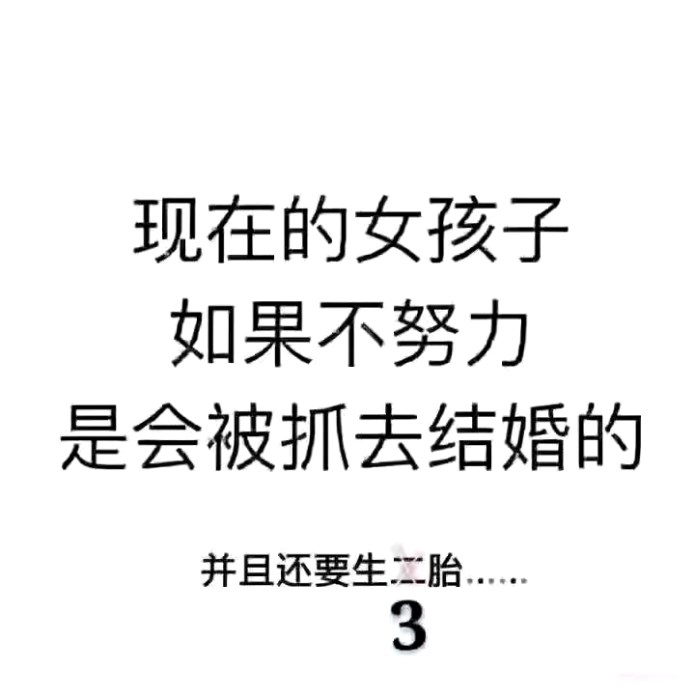

For the past three years (this was the fourth event), Hougongfang has been promoting “middle age day (中年节).” The event was filmed before a live audience to be broadcast on May 25, which is the day they’ve designated for the new holiday. I know, you’re probably thinking: didn’t China establish May 25 as University Mental Health Day (525心理健康节)? And the answer is yes. And to answer your unasked question: yes it explains so much about contemporary China when today’s middle-aged magnates are promoting their contributions to society and the value of their experience on a day that had been set aside to address the mental health of the country’s anxious, overworked and often suicidal college students.

Thoughts (not all of them generous because remind you of US boomers much) below:

Continue reading