Most are aware that the area we once knew as “Baishizhou” was located north of Shennan Road, comprising four villages–Shangbaishi, Xiabaishi, Tangtou and Xintang. The neighborhood’s name derived from the “Baishizhou” subway station. In turn, the station was named for the historical Baishizhou, a mudflat or sandbank, which was located south of Shennan Road. Historically, our Baishizhou was a continuation of historic settlement patterns, while Baishizhou Village seems to have emerged more recently. Nevertheless, the demolition of our Baishizhou has led to the emergence of a new Baishizhou and this new Baishizhou has a telling (and frankly distressing) general layout. Below, I give a brief overview of the layout and then a brief history of the place name, Baishizhou. And yes, its more speculative than conclusive. Reader be warned.

The demolition of our Baishizhou in conjunction with Covid protocols have led to a micro-restructuring of the area. The new Baishizhou (which boasts a strategically placed name stone) broadly speaking now comprises three sections–the outer rim that faces the gated communities along Shizhou Middle Road, the urban village, and the out rim that faces Baishi Road. The defining feature of this geography is the isolation of the village itself from the larger environment. The allies that formerly linked every alley to the city proper have been gated and in some cases cemented shut, leading to a situation in which one needs to know where gates are open in order to enter the village. Moreover, within the village itself, gates have been added, allowing for isolation of sections within the village.

In the section facing the gated communities of Shizhou Middle Road, large restaurants have been established. Some occupy the large building that was the intended main building of a sciencey-futuristic theme park that never opened, while others occupy the entire first floor of the handshake buildings along the road. This section is obviously the most prosperous of the new Baishizhou.

Inside, the Baishizhou village itself, the main street still bustles, but it is obviously less prosperous. Moreover, it is obviously now an isolated neighborhood and no longer a destination for anyone who wanted to slip through an alley and go shopping. In turn, the back section which faces Baishi Road is almost deserted, despite the large formal gate. This not only due to Covid closing of allies, but also because the main housing estate, 京基·东堤园 and shopping mall 京基百纳 were gated off from Baishizhou when they were first built over a decade ago. Just an aside “东堤园” literally means “Eastern Dyke Estates,” which gives a sense of how that area was built up on land reclaimed from the original baishizhou, or White Stone sandbank, historically a site for docking sampans and taking care of oyster fields. Of course, there is a fourth section, the interior buildings that were originally crushed up against Window of the World, (begging the question: do we get to speak of Baishizhou quartiers now?)

So, what’s in the name 白石洲村, rather than just 白石洲, the neighborhood that thrived around the eponymous subway station? A bit of historic background and conjecture:

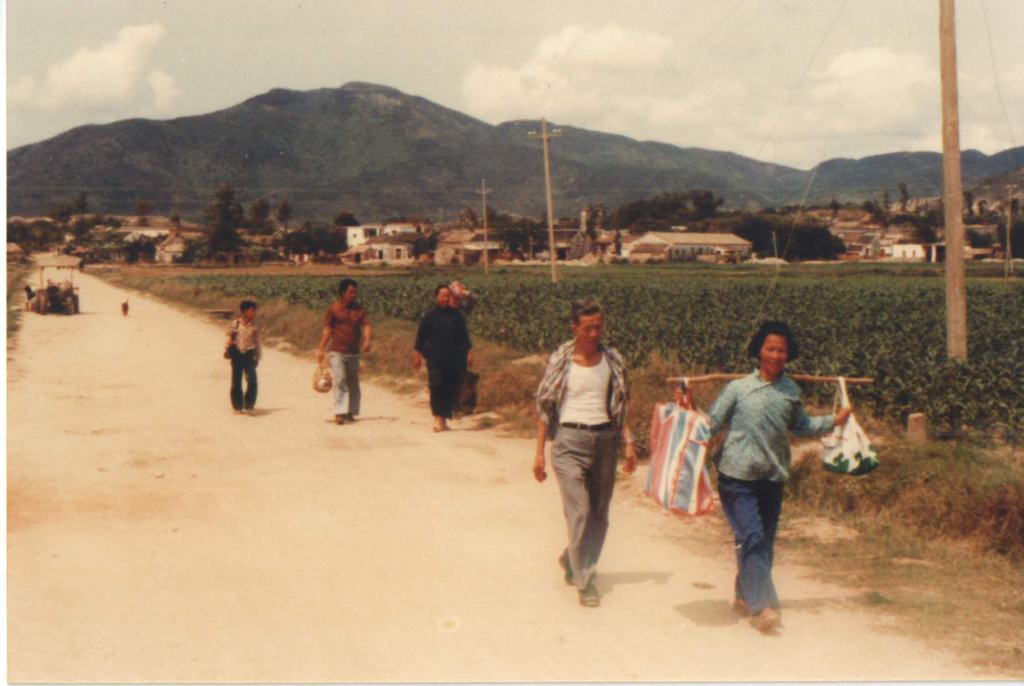

Historically the northern section has been more prosperous than the south. Both Baishi (White Stone) and Xintang Villages appear in the 1688 Xin’an Gazetteer. “Shangbaishi” and “Xiabaishi” mean upper and lower White Stone villages. The villages were named after a nearby white stone, which could be seen from the water, suggesting the littoral orientation of the landscape. Nevertheless, the villages had paddies, in addition to docks, making them “punti / bendi 本地” in the sense defined by Helen Sir and David Faure in Down to Earth: The Territorial Bond in South China. So, the relative prosperity of our Baishizhou was a continuation of the historical cultural geography where people settled on land near their fields. Indeed, pictures from the 1980s show villagers walking from the hills, through fields to Shennan Road, which was a dusty road, still under construction in the downtown area (image below).

In contrast, White Stone sandbar–the literal translation of Baishizhou–was historically a site for docking boats that wanted to land here. It was important because Baishizhou–the sandbar, not the village–was the maritime “backdoor” to occupying the county seat at Nantou. During the Sino-Japanese War it was an important site for defending access to the mainland, but even before that was often a landing site for British citizens on walking tours of the mainland. A US map from 1954 (below) shows the location of the P’aishih-chou Mud relative to Par-shih and Hsin-t’ang Villages

I have first discovered mention of people living on the White Stone Sandbar (Baishizhou) as part of the larger Shajing Oyster Commune, which was established in 1958. My suspicion is that Baishizhou Village as a recognized village, rather than as an informal landing area was established sometime during the 1950s, when the coastline was being restructured first for national defense, then for oyster production and then as part of the Shahe Farm. (This conjecture is unconfirmed by conversation because the few people I have thought might know have all said “not sure” when asked. The 1986 edition of the Shenzhen Place Name Gazetteer just says that the Village is so-named because it was built on the eponymous sandbar. But seriously, who builds a village on a sandbar? All the other places that I have run into with a similar geography–built on sands or dykes rather than near a mountain–were formally established during the 1950s when the area was restructured and integrated into national production).

All this to say, Baishizhou Village qua urban village manifests the history of Reform and Opening and 1950s administrative restructuring much more than it does the history of the area. Nevertheless, it has already been figured (like many urban villages) as a sign of deep history, misdirecting many attempts to write a living cultural geography of the area.