It turns out that Covid-19 is good to think if your goal is to understand ‘China’ as imagined, perceived and, of course, enforced. (Winning?) After all, even if there are no countries outside are heads, nevertheless, there are test stations, checkpoints, police, and all sorts of social monitoring. Moreover, how different groups–both at home and abroad–are responding to the lockdown shows up interesting aspects of my experience in Shenzhen. So, I’m providing a round-up of some of the Covid related blogs, essays and books that I’ve been reading to embed Shenzhen’s experience into national and international discourses about biological governance, moral geography and new forms of self expression. And yes, they’re all over the place because we don’t really know how the ground has shifted. Moreover, I find comparison and contrast both necessary and useful because the intellectual and political challenge is to provide rich, on the ground accounts of lived experience within and against political-economic systems that are (to use a harsh neologism) always already glocal–the suffering caused by Covid-19 is universal, but responses to and cultural expressions of pain have been highly specific.

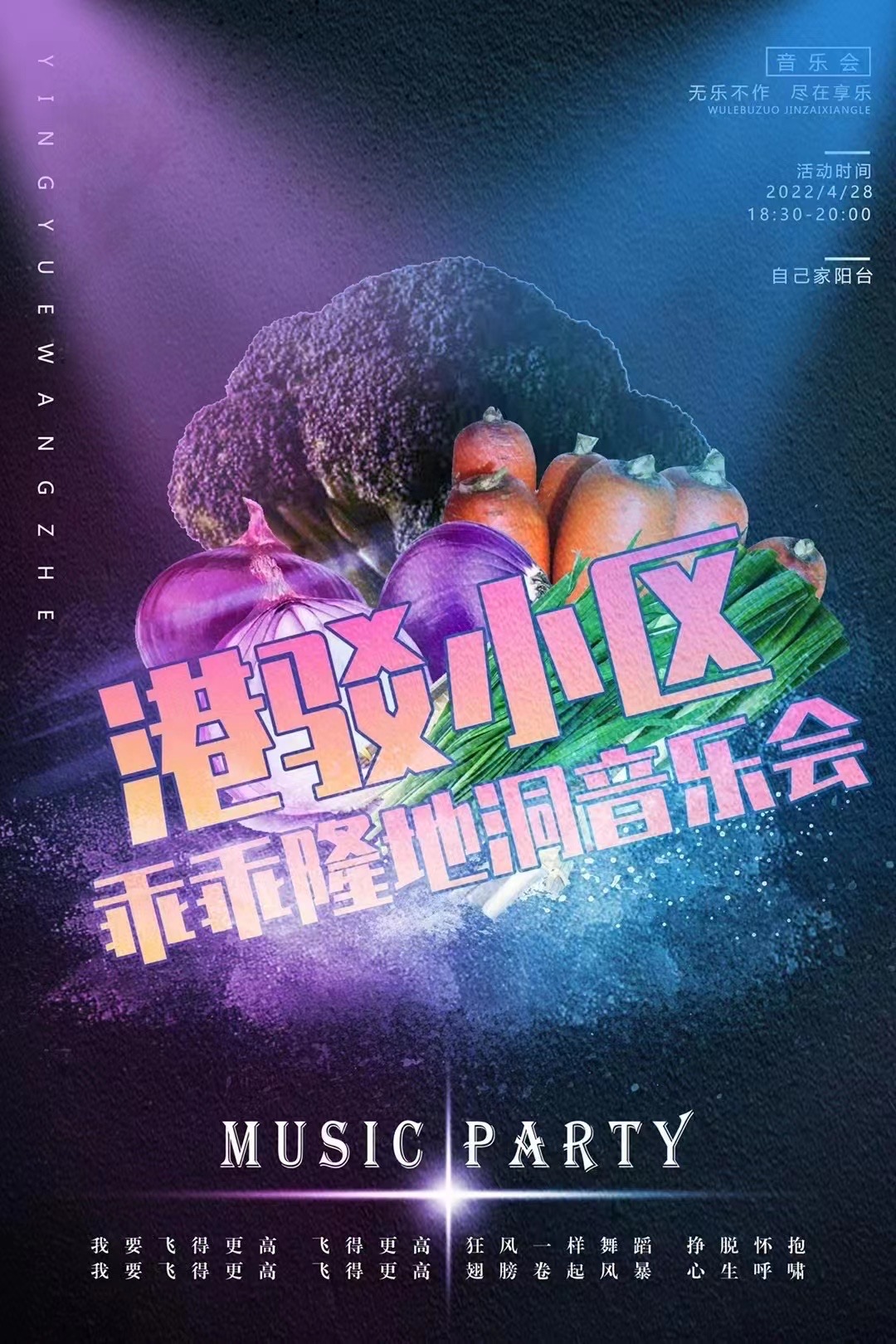

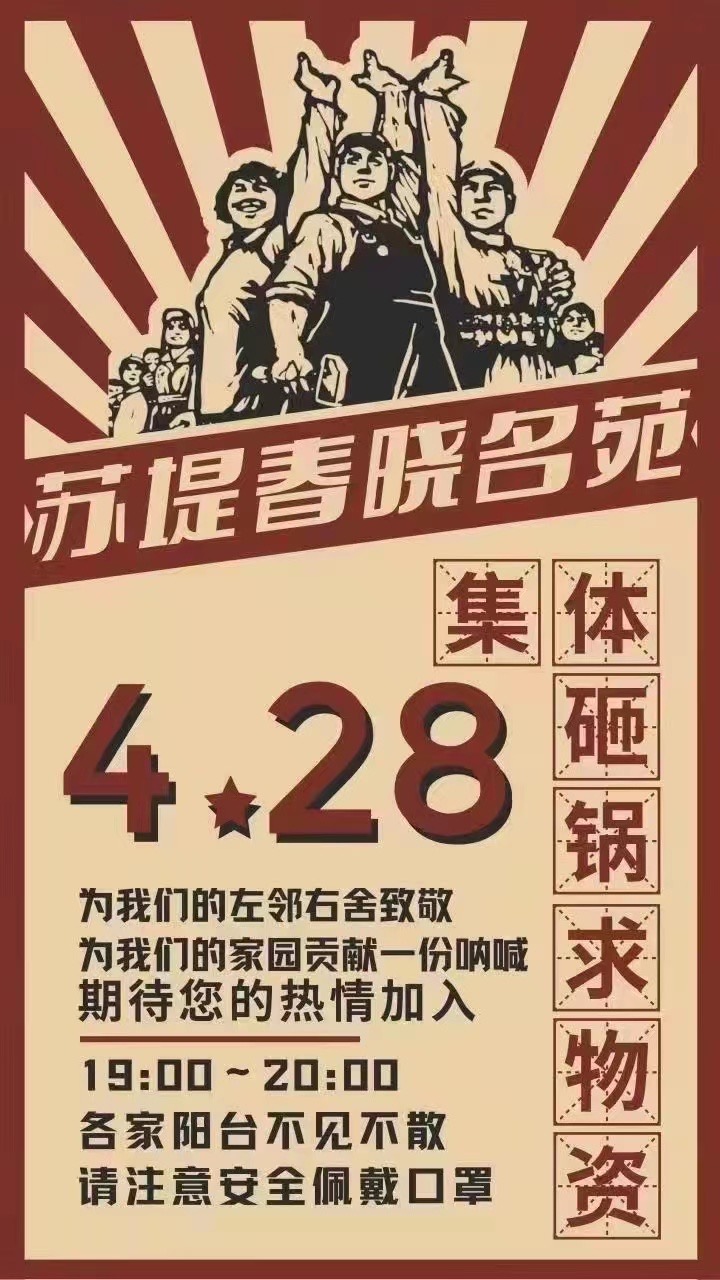

The cartoon caption which comes via the 2022 Shanghai lockdown reads, “Who dares call a meal with pig feet and bear’s claw anything less than a feast? You can’t hide that we’re living in a flourishing age.”

Continue reading →