An essay written for Open Democracy is now online. Here’s the introduction. Over the next few days, I will put up the sections on Nantou, Luohu-Dongmen, Xixiang, and Baishizhou.

Laying Siege to the Villages: Informal Urbanization in Shenzhen

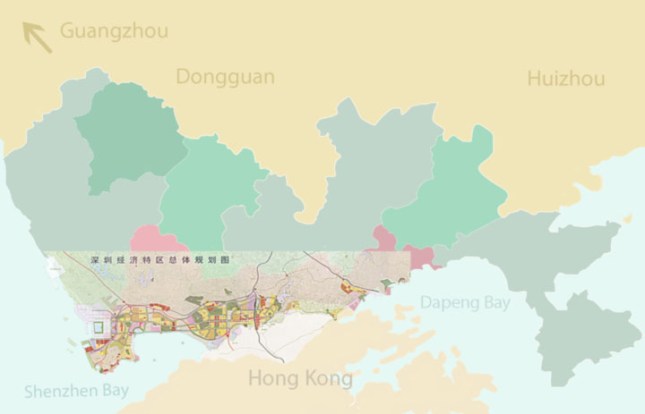

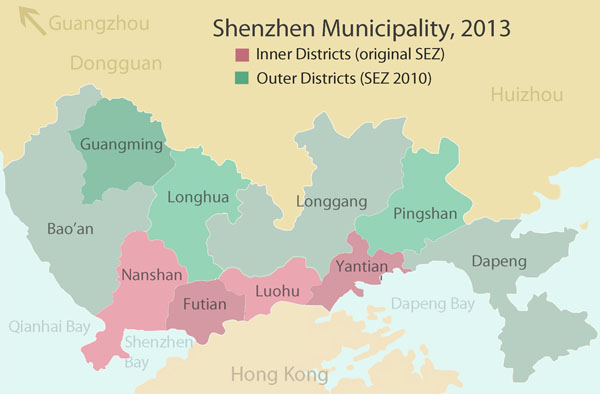

Although Shenzhen is famous for its “urban villages” or “villages in the city” (城中村 chengzhongcun), nevertheless, in 2004 Shenzhen became the first Chinese city without villages. Full stop. This fact bears repeating: legally, there are no villages in Shenzhen. As of 2007, Shenzhen Municipality had a five-tiered bureaucracy consisting of the municipality (市shi), districts (市区shiqu), new districts (新区 xinqu), sub-districts or streets (街道jiedao), and communities (社区shequ). Since 2010, the Districts have been known as the inner districts and outer districts, reflecting when they were incorporated into the Shenzhen Special Economic Zone (SEZ) (Map 1).

Under Mao, rural areas were China’s revolutionary heart and “villages surrounded the city (农村围绕城市)” was an explicit political, economic, and social strategy for revolutionary change. The Mandarin expression “surrounds (围绕)” can also be translated as “lays siege to”, highlighting the rural basis of the Chinese Revolution. Early Chinese Communists had followed the Russian example and entered cities to organize workers. However, when Nationalist forces led by Generalissimo Chiang Kai-shek violently suppressed Communist organizations in Chinese cities the Communists retreated to the countryside. Moreover, communists and local people identified colonial ports such as Hong Kong with the proliferation of traitors, parasitic merchants, and corrupt officials. Consequently, while Marx claimed that modern history was the urbanization of the countryside, the Chinese revolution aimed to re-occupy and purify the cities. Beginning in 1927 until the occupation of Beijing in 1949, the Communists organized rural resistance to both Japanese invaders and Nationalist hegemony, literally surrounding the cities with an estimated 5 million rural soldiers.

The establishment of Shenzhen signaled the beginning of a new era in Chinese history – “cities surround the villages (城市围绕农村)”, an expression which Shenzhen urban planners and architects have self-consciously used to describe urbanization in the city. Historically, there were legally constituted villages in Shenzhen. The present ambiguity over the status of villages and villagers is a result of contradictions between Maoist economic planning and post-Mao liberalization policies. Under Mao, the country was segregated into rural and urban areas. In rural areas, villages were designated production teams and organized into work brigades that were administered by communes. Communes had to meet agricultural production quotas that financed industrial urbanization and socialist welfare policies in cities, which were tellingly defined as “not-agrarian (非农feinong)”. Importantly, the hukou or household registration policy literally kept people in place – the allocation of food, housing, jobs, and social welfare took place through hukou status. Food and grain coupons were city-specific, for example, and a Shanghai meat coupon could not be legally exchanged in a neighboring city, let alone Beijing. In rural areas, however, communes and production brigades provided neither food coupons nor housing to members. Instead, brigade members produced their own food (usually what was leftover after production quotas had been met) and built their own homes or rural dormitories as they were known in the Maoist system.

In 1979, when the Guangdong Provincial Government elevated Bao’an County to Shenzhen Municipality, the area was rural, and the majority of its 300,000 residents had household registration in one of 21 communes, which were further organized into 207 production brigades. However, hukou status notwithstanding, the integration of brigades and teams had not been complete and members continued to identify with traditional village identities. Although the names of Shenzhen’s current districts were the names of ten of the larger communes, for example, with the exception of Guangming, they were also historically the names of large villages that had been the headquarters for communes. In 1980, the Central government further liberalized economic policy in Shenzhen by establishing the area that bordered Hong Kong as a Special Economic Zone (SEZ). This internal border was known as “the second line”, in contrast to the Sino-British border at Hong Kong or “the first line”. The re-designation legalized industrial manufacturing and foreign investment (primarily from Hong Kong) in the new SEZ. Outside the second line, Shenzhen Municipality established New Bao’an County, which was still legally rural and administered through collective institutions.

The elevation of Bao’an County to Shenzhen Municipality created an anomalous situation within Socialist China because the administrative division of Shenzhen into the SEZ and New Bao’an County only legalized new economic measures; it did not transfer traditional land rights from brigades and teams to the new municipal government. Instead, the first task of urban work units that came to the SEZ was to negotiate the equitable transfer of land rights from the collectives to the urban state apparatus. The goal was to insure that rural workers would continue to have space for housing and enough land to ensure agricultural livelihoods. And this is where historical village identities reasserted themselves. In theory, the urban work units negotiated with brigade and team leaders to transfer the administration of land from the rural to the urban sector of the state apparatus. In turn, the brigades and teams would continue to produce food for the new urban settlements. In practice, however, brigade and team leaders acted on behalf of their natal villages and co-villagers, asserting a pre-revolutionary social identity.

The legal slippage between collective identity within China’s rural state apparatus and collective identity through membership in a traditional village arose because although the Constitution and subsequent Land Law of 1986 stated that rural farmland belonged to the collective, neither document went so far as to define what a collective actually was in law. Indeed, the difference between rural and urban property rights has been the foundation for post-Mao reforms, first in Shenzhen and then throughout the country. In 1982, the amended Constitution formally outlined the different property rights under rural and urban government. According to Article 8 of the Chinese Constitution:

Rural people’s communes, agricultural producers’ co-operatives, and other forms of co- operative economy such as producers’ supply and marketing, credit and consumers co-operatives, belong to the sector of socialist economy under collective ownership by the working people. Working people who are members of rural economic collectives have the right, within the limits prescribed by law, to farm private plots of cropland and hilly land, engage in household sideline production and raise privately owned livestock. The various forms of co-operative economy in the cities and towns, such as those in the handicraft, industrial, building, transport, commercial and service trades, all belong to the sector of socialist economy under collective ownership by the working people. The state protects the lawful rights and interests of the urban and rural economic collectives and encourages, guides and helps the growth of the collective economy.[1]

In contrast, according to Article 10, land in cities is owned by the State:

Land in the rural and suburban areas is owned by collectives except for those portions which belong to the state in accordance with the law; house sites and private plots of cropland and hilly land are also owned by collectives. The state may in the public interest take over land for its use in accordance with the law. No organization or individual may appropriate, buy, sell or lease land, or unlawfully transfer land in other ways. All organizations and individuals who use land must make rational use of the land.[2]

The contradiction between the fact that villages no longer have legal status in Shenzhen and their traditional claims to land rights and social status – both of which are recognized by Shenzhen officials and residents – has constituted a serious political challenge for Shenzhen officials, who have viewed the villages as impediments to “normal (正常)” urbanization. Officials have defined “normal” urbanization with respect to the Shenzhen’s Comprehensive Urban Plan, which has already gone through four editions (1982, 1986, 1996, and 2010). In other words, “normal” urbanization has referred either to formal urbanization or informal urbanization that has secured legal recognition. In contrast, Shenzhen’s urban villages emerged informally as local residents not only built rental properties to house the city’s booming migrant population, but also developed corporate industrial parks, commercial recreational and entertainment centers, and shopping streets. As of January 2013, for example, it was estimated that half of Shenzhen’s 15 million registered inhabitants lived in the villages. Moreover, these densely inhabited settlements also provided the physical infrastructure that has sustained the city’s extensive grey economy, including piecework manufacturing, spas and massage parlors, and cheap consumer goods.

In Shenzhen, urban villages have been the architectural form through which migrants and low-status citizens have claimed rights to the city. Importantly, informal urbanization in the villages has occurred both in dialogue with and in opposition to formally planned urbanization. On the one hand, informal urbanization in Shenzhen urban villages has ameliorated many of the more serious manifestations of urban blight that plague other boomtowns. Unlike Brazilian favelas, for example, Shenzhen urban villages are not located at the edge of the city, but rather distributed throughout the entire city and many urban villages occupy prime real estate. Consequently, Shenzhen’s urban villages have been integrated into the city’s infrastructure grid and receive water, electricity, and also have access to cheap and convenient public transportation. Moreover, as Shenzhen has liberalized its hukou laws, urban villages have also been where migrants have access to social services, including schools and medical clinics. Thus, Shenzhen’s urban villages have provided informal solutions to boomtown conditions. On the other hand, the lack of formal legal status of urban villages and by extension the residents of urban villages has allowed the Municipality to ignore residents’ rights to the city via the convenience of centrally located low-income neighborhoods. In fact, the ambiguous status of urban villages became even more vexed in 2007, when the Shenzhen government initiated a plan to renovate urban villages. It has been widely assumed that the government promulgated the new plan in order to benefit from the real estate value of urban village settlements. Critically, the Municipality’s plans for urban renovation compensated original villagers while ignoring the resettlement needs of migrant residents. Thus, the status of at least half of Shenzhen’s population suddenly entered into public discourse as it has become apparent that although the urban villages resulted from informal practices, nevertheless, they have been the basis for the city’s boom.

Ruralization: The Ideology of Global Inequality

Each of the sections in this essay explores the social antagonisms that have emerged through the transformation of Bao’an County into Shenzhen Municipality via informal urbanization in the villages. The point is that Shenzhen’s so-called urban villages are in fact urban neighborhoods that grew out of previous rural settlements through rapid industrial urbanization. Nevertheless, the designation of “rural” or “village” still clings to these neighborhoods, making them the target of renovation projects and ongoing calls for upgrades. In turn, these calls justify razing neighborhoods and displacing the working poor with upper and upper middle class residential and commercial areas. Recently, Caiwuwei was razed and rebuilt as the KK 100 Mall, while Dachong was razed and as of 2013 a new development under construction. Hubei, the old commercial center in Luohu has been designated as the next major area to be razed, while in late 2012, the Shenzhen Government and Lujing Developers announced their intention to raze and rebuild Baishizhou as a centrally located luxury development.

In Shenzhen, ruralization is primarily an ideological practice through which neighborhoods for the working poor and low-income families have been created by denying the urbanity of these neighborhoods and their residents. In this practice, the city’s rural history is invoked to demonstrate that neighborhoods which grew out of villages are continuations of the village, rather than the results of informal urbanization. Indeed, there are few actual remains of Shenzhen’s rural past. Instead, the target of official rural renovation projects are in fact the informal housing and industrial parks that were built roughly between the mid 1980s through 2004/5, when the municipal government began actively preventing informal construction.

In addition, I have included annotated maps and photographs that illustrate the spatial and social forms of these different contradictions have taken. With respect to recent Chinese history, this level of specificity aims to make salient how Shenzhen enabled national leaders to reform Mao’s rural revolution. With respect to contemporary research on mega-cities, this essay draws attention to the ways in which architectural forms have facilitated neoliberal urbanisms that exclude the poor from desired futures.