A five-part essay, “Laying Siege to the Villages” has been published online at Open Democracy. Here’s part two on the Nantou Peninsula.

2. Concentric Occupations: Nantou Peninsula

The built environment of Shenzhen urban villages references three historic moments – late Qing and Nationalist-era rural society, Maoist collectivization, and post Mao reforms. Spatially, this history has been expressed as concentric occupations, with the oldest sections being first appropriated and then surrounded by newer developments. In turn, older settlements have been downgraded and converted into low-income neighborhoods. Locally, this process has been called, “cities surround the countryside”, which not only resonates ironically in post Mao China, but also identifies poverty with rural status. Maoist theory and practice had identified cities with all that was foreign and reactionary, and villages with all that was truly national and revolutionary. In contrast, the elevation of Bao’an County to Shenzhen Municipality began the administrative transvaluation of the rural-urban relations, which was formalized in 1982 Chinese Constitution.

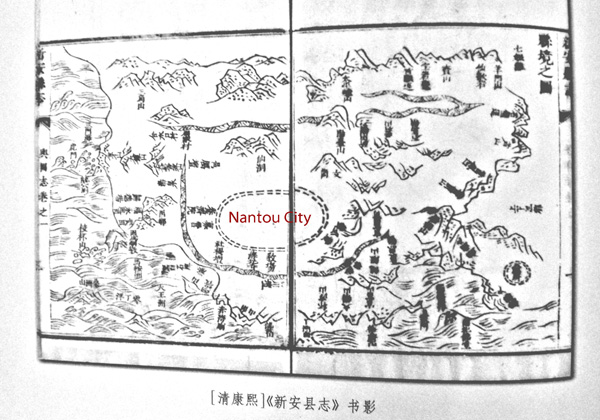

Over 1,000 years ago, salt fields were developed in the Shenzhen-Hong Kong area, and the yamen for the local salt intendant was located on the Nantou Peninsula. The area was also famous for its oyster and pearl production. The peninsula provided protected harbors and access to Guangzhou via the Pearl River. During the Ming dynasty, the Shenzhen-Hong Kong area was called Xin’an County and Nantou City was designated its County Seat. Located on the southeastern banks of the Pearl River, Xin’an was historically poorer than the counties on the eastern banks. Nevertheless, the harbors of the Pearl River’s eastern coastline were significantly deeper than those on the western coastline. Consequently, Chinese maritime access to the South China Sea traditionally went through Humen (in neighboring Dongguan) and Nantou. Indeed, Zheng He’s fleet stopped at the Tianhou Temple in Chiwan Harbor on their voyages of exploration (1405-1433), which took the Ming explorer as far as Africa. After the Ming ban on ocean travel made it possible for pirates to control the South China Sea, Guangzhou remained the southern gate to China and the ports on the eastern coast of the Pearl River became even more coveted by international traders (map 2).

Map 2: Xin’an County Seat in the Reign of the Kangxi Emperor (1661-1722)

By the late 18th Century, Guangzhou had not only become and important financial center, but also the center of opium trade. The first Opium War ignited when Lin Zexu dumped the opium stocks of British traders in the Pearl River. In turn, the traders successfully pressured the British government to use military means to secure compensation for their losses. China’s defeat in the Opium Wars resulted in British colonialization of southern Xin’an, including Hong Kong Island, the Kowloon Peninsula and the New Territories. The Sino-British border was drawn along the Shenzhen River and passed just south of Shenzhen Market (map 3). The laying of the Kowloon-Canton Railway in 1913 further shifted the flow of goods and people toward Hong Kong and away from Nantou. Small-scale trade between settlements on the Pearl River continued, although Nantou no longer played a dominant role in the regional political-economy. Instead, Shenzhen Market, the first station on the Chinese side of the KCR became the political and economic center of Xin’an County, which was renamed Bao’an at the start of the Nationalist era.

Map 3: Riparian Trade Routes, Nantou City, and British Incursions

In fact, the establishment of Shenzhen explicitly invoked colonial history, making the return of Hong Kong to Chinese sovereignty one of the key political impulses behind economic liberalization. Maoist modernization of Nantou, for example, included a two-lane road (today known as New South Road), which was laid parallel to the ancient South Gate Road and connected the peninsula villages to the national railroad and highway system. In the post Mao-era, however, state investment has aimed to urbanize the area, rather than to integrate rural settlements into the state apparatus. Land reclamation of Pearl River coastline gives the clearest indication of the scale and ambition of these plans – replacing Hong Kong and possibly even Guangzhou in the global organization of South China trade.

The reform-era transformation of the Nantou Peninsula illustrates the broad contours and social contradictions that have characterized “cities surround the countryside”. During the Ming Dynasty, a pounded earth wall enclosed Nantou, but by the time of the first Opium War, the wall had crumbled into disuse and only the southern and eastern gates still stood. A road stretched from the decrepit Southern Gate and along the coast of the Pearl River to Nanshan Village, which was located at the foot of Nanshan Mountain. Between Nantou Old City and Nanshan Village six villages – Guankou, Yongxia, Tianxia, Xiangnan, Beitou, and Nanyuan – claimed land that included access to the Pearl River, a portion of South Gate Road that they identified as Village Main Street, and farmlands that extended inland. However, through land reclamation and the emplacement of a grid of four- and six-lane roads, such as Qianhai Thoroughfare, Shenzhen’s rural origins have been surrounded and isolated South Gate Street neighborhoods from the larger city (map 4).

Map 4: Cities Surround the Countryside: The Nantou Peninsula