I went to the opening of Li Liao (李燎)’s solo exhibition, Labor (劳动) at the Pingshan Art Museum. Li Liao lives and works in Shenzhen, where he and his wife are working off their large mortgage. When his wife decided she wanted to start her own company, Li says that he decided to work as a delivery boy in order to pay off one month’s mortgage payment. It took him six months to earn his keep, so to speak.

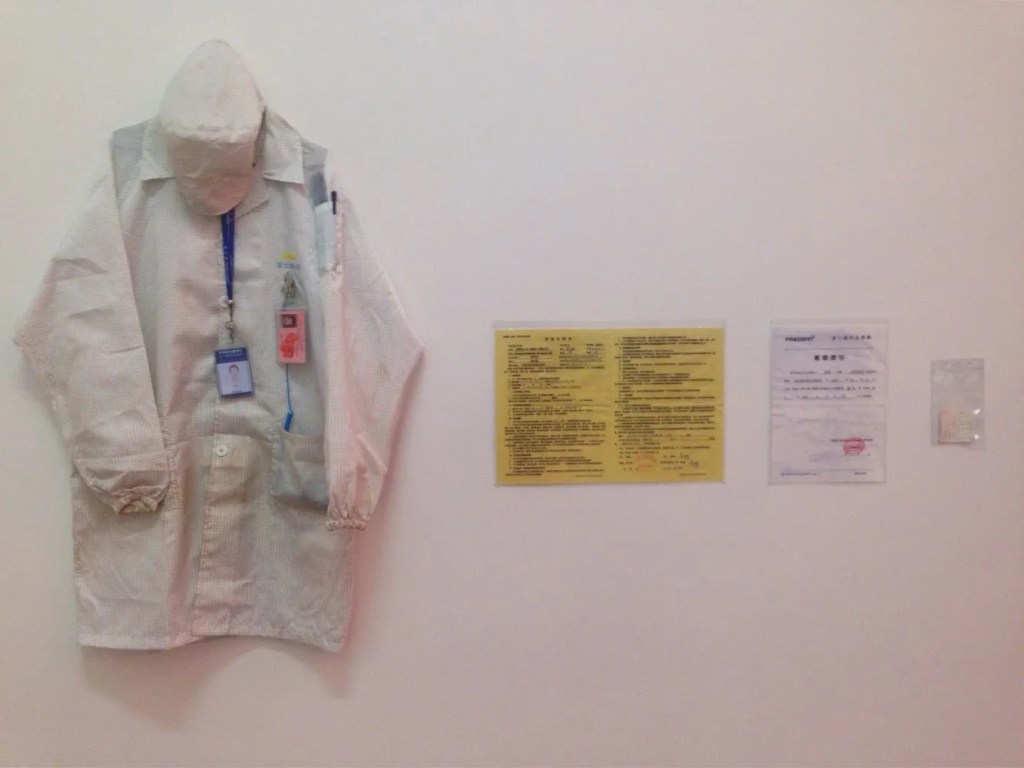

The exhibition was displayed on two floors in the museum, with most objects on the first floor and viewing platforms available on the second. The main objects included: Li Liao’s uniform, moped, and receipts from his tenure as a delivery boy; installations of the different sidewalks that delivery people traverse over the course of their day, and physical structures made out of the obstacles that filled the sidewalks. There were also videos from a camera that had been attached to his helmet. So, an exhibition of artifacts from a six-month performance.

Labor is of a piece with his previous work. Li Liao’s most famous work is Consumption (消费, 2012), which was displayed at the Beijing Ullens Center for Contemporary Art’s current exhibition of emerging artists, ON | OFF in 2013. The display was a collection of artifacts — a uniform, security badges, his contract and an iPad — from his 45-day tenure as a circuit board inspector at the Shenzhen Foxconn campus. He bought the iPad with the wages he earned on the job. The piece was widely reported on, even getting an essay in The New Yorker. The piece was especially evocative because the ON|OFF exhibition occurred after the spate of suicides at Foxconn.

I’m interested in Labor for two reasons: first the relationship between art and labor is one of the ongoing themes in works in and about Shenzhen and second, the nature of labor in Shenzhen has fundamentally changed since the city was known as the world’s factory. Indeed, the distance between Consumption (2023) and Labor (2012) is telling: in roughly a decade, factory workers have visibly disappeared from the landscape being replaced by service workers, especially the delivery people who race through the city sidewalks on mopeds.

The relationship between art and manufacturing labor first made its appearance through engagement with the painters of Dafen Oil Painting Village. The complexity of this relationship was foregrounded in the Dafen Lisa–This is not the Mona Lisa installation at the 2010 Shanghai Expo, which begged the question: are Dafen painters artists or are they line workers? The question arose just as Shenzhen was deindustrialising, but was still largely looked upon as the “world’s factory.” Indeed, as Winnie Wong has documented, this theme has haunted many western engagements with Dafen, where the question of the authenticity of art has been an ongoing source of angst. (Does the creative moment exist in the concept or is it found in skilled execution? If we can think strange things but must hire others to execute are vision are we still artists or are we bosses? If we are artists, then what is the role of the people who actually make the work?)

Urbanus addressed these questions by commissioning 1,000 painters in Dafen to each paint one canvas of a pixelated and enlarged reproduction of the Mona Lisa. The 43-meter long 7-meters high installation was the centerpiece of the Shenzhen Pavilion, which the architectural firm curated, bringing their ongoing interest in urban villages to an international audience.

Five years after the Shanghai Expo, the V&A Shekou team curated Unidentified Acts of Design for the 2015 Shenzhen-Hong Kong Bi-City Biennale of Urbanism\Architecture (UABB). The display comprised eight stories about how Shenzhen has produced a range of products, including copy paintings, tech products, and virtual realities. The V&A exhibit broadened the understanding of creativity from the perspective of production, and from this perspective Dafen painters have a specialized niche within a larger cultural economy. However, the centrality of Shenzhen to global manufacturing was still central to the Unidentified Acts.

In contrast, Labor does not acknowledge the manufacturing economy. Instead, it highlights how Shenzhen has oriented itself to supporting the creative (especially design) economy. Creativity, in this sense, is now highly conceptual. In fact, one of the stories in Unidentified Acts was how shifu (师傅 master craftsmen) mediated between foreign designers and the factory floor, transforming designs into manufacturable products. A shifu takes a shoe design, for example, and produces the production specs. This often involves tweaking the original design. However, at the time that curators Brendan Cormier and Luisa E Mengoni did research in Shenzhen, there were still factories not only in the outer districts, but also prototyping factories in Baishizhou. Of course, the Baishizhou factories were demolished in 2016 and since then, Longgang and Longhua have reoriented to high-tech and AI. Indeed, even the Foxconn and Huawei campuses in Bantian emphasize their R&D capacity, rather than what they’re actually producing.

Also of note: two contemporaneous events frame the importance of Labor. First, the current exhibition up at the Dafen Art Museum (also designed by Urbanus) is the Morandi retrospective, which is being promoted as building a bridge between China and Italy. Second, the closing of OCAT and the turning away from high art in Overseas Chinese Town model of real estate development. In other words, Labor at PAM and the Morandi retrospective at DAM not only signal that development has shifted from the inner to the outer districts, but also that art and culture is now explicitly under the purview of the state. In the inner districts, there are still small, independent galleries. But. Now only various governments are funding large-scale innovative art exhibitions.

Pingback: Singleton Take-out | Shenzhen Noted