Googling for information about environmental conditions in Shenzhen, I noticed that the distinction between delta and estuary has facilitated a disturbing separation between conversations about economic miracles and ecological disasters in Southern China. When I googled Pearl River Delta, I stumbled upon articles about economic development. In contrast, when I googled Pearl River Estuary, I came upon articles about the seriousness of our situation.

Here’s the rhetorical rub: Ecologically, deltas and estuaries co-evolve. However, through linguistic convention, the words delta and estuary refer to different aspects of this process. The word delta draws our attention to what’s happening on land, while the word estuary reminds us what happens in places where fresh and salt water mix. In other words, how we locate Shenzhen – either in an estuary or on a delta – has already determined whether our conversation will most likely be about environmental or economic issues.

So, by emphasizing the Delta in conversations about South China, what do English speakers leave out? The fact that in an October 19, 2006 press release, the United Nations Environment Programme announced that the Pearl River Estuary was a newly listed dead zone, where nutrients from fertilizer, runoff, sewage, animal waste, and the burning of fossil fuels trigger algal blooms. The most common algal bloom in the Pearl River Estuary is “red tide”, a colloquial way of saying HAB – harmful algal bloom of which the most conspicuous effects are the associated wildlife mortalities among marine and coastal species of fish, birds, marine mammals and other organisms.

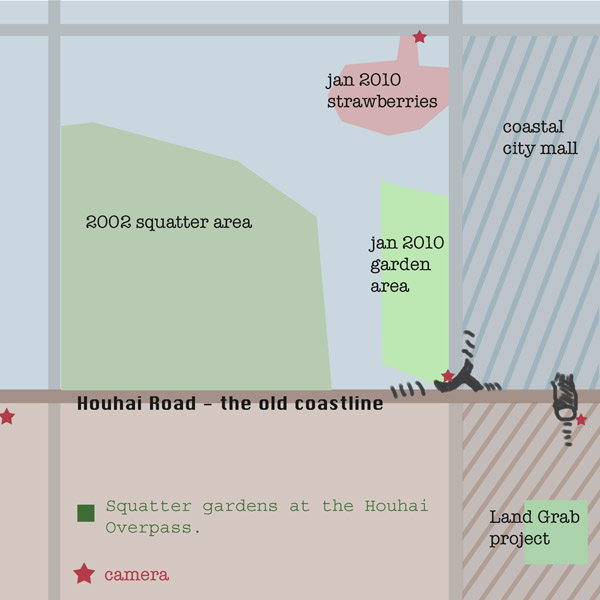

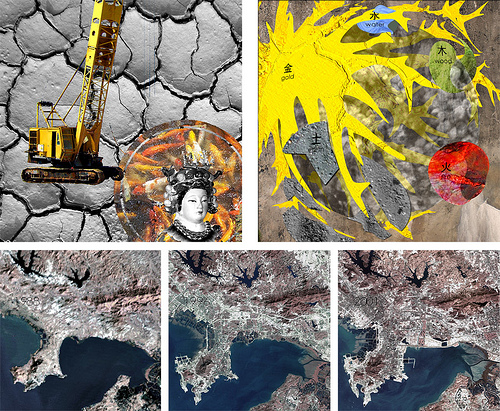

What else do we English speakers miss? The ongoing houhai land reclamation and associated siltation, which is damaging coastal Mangrove forests. In the panel Gilded Coast from Prosthetic Cosmologies, I used images from the NASA Scientific Visualization Studio to draw attention to this process. The SVS images were taken in 1988, 1996, and 2001. Taken in December 2008, a recent Earth Snapshot from Chelyis shows how more has changed in the past seven years. The Chelyis image also contextualizes the SVS images within the delta/estuary. Compare the levels of siltation and environmental transformation below:

More importantly, the Cheylis explanation identifies both Guangzhou and Hong Kong, but not Shenzhen. This omission is disturbing not only because Shenzhenhas been the most active land reclaimer in the region, but also because it pre-empts inclusion of Shenzhen – as well as Dongguan, Foshan, Zhongshan, and Macau – in conversations about how to both clean-up and enrich the region. (This omission dovetails into dim sum with the Swiss writers, who were shocked by how developed Shenzhen actually is. I keep asking myself: how do westerners miss Shenzhen? And it keeps happening…)

Incidently, the Chinese character 洲 (zhou) further muddies rather than bridges waters between English and Chinese conversations about the environmental consequences of economic development. The two parts of zhou are: the three-dot radical for water and 州 (zhou), a sound component which is composed of the pictograph for river with three dots. According to my dictionary, a 洲 is a continent or an island, so a delta/estuary is actually a three-cornered continent island or 三角洲, while the character is two-thirds full of water. This means googling 珠江三角洲 brings up a different mix of economic and environmental articles than does an English attempt.