Yesterday, I participated in an organizational meeting for a public talk on Shenzhen University. The meeting was held at the Qinghua Park (清华苑), the design firm headed by Luo Zhengqi former SZU president and members of the original SZU design team that left the University when he did (in post June 4th restructuring).

Yesterday, I participated in an organizational meeting for a public talk on Shenzhen University. The meeting was held at the Qinghua Park (清华苑), the design firm headed by Luo Zhengqi former SZU president and members of the original SZU design team that left the University when he did (in post June 4th restructuring).

The planning of the SZU campus interests because it represents a unique moment in the Municipality’s history. Members of the Architecture Department as well as students in the first graduating classes actively participated in the design and construction of the campus. Indeed, Teacher Luo held on campus competitions to design dormitories and other buildings on campus.

According to Teacher Liang, who was in charge of the project, the animating principle of the design was a “return to nature (回到自然)”. She defined this return to nature in terms of freedom of spirit . For Teacher Liang, “nature” meant “human nature” as an extension of natural order.

Teacher Luo joked that the reason the design of the SZU campus had succeed was because they hadn’t done anything, a reference to the Daoist value of “no action (无为)”. On Teacher Liang’s understanding, freedom allows human beings to express and recognize human nature or art through the creation of material objects and the modification of the environment. She emphasized that neither economic nor social limits determined the form and meaning of an object or space, but rather human intention and the liberation of the human spirit.

Eyes sparkling, Teacher Liang illustrated her understanding of the kind of freedom at SZU with a joke, “There was no summer vacation at SZU.” Everyone was busy at one of the many construction projects, none of which were landmark buildings. Instead the campus layout reflected the ethos of communal construction toward a common goal — education for a new kind of citizen, one who made creative break throughs rather than repeated standardized forms.

For example, the main gate was set at an oblique angle, rather than along a cardinal axis, which was and remains a standard design practice for a university. In addition, early SZU was not walled off to create links between the campus and society. Moreover, the library held pride of place in the university commons, rather than a Ceremonial Hall for university meetings. In this sense, Teacher Liang defined freedom not as “freedom to do whatever I want (自由放肆)”, but rather a self-regulating freedom that creatively responded to community needs (自由自律).”

The second planning value that Teacher Liang emphasized was humility (谦卑). Humility took two explicit forms. First, layout emphasized users’ convenience, rather than centralization. Thus, staff offices and classrooms were located on either side of the central library, while student dormitories were placed adjacent to classrooms and within a 10-minute walk to the library. Staff housing and facilities were located furthest from the central commons. To further promote cross disciplinary conversations, students were not housed by major, but by year.

Second, large swathes of land were left open for future use. This open land, which included a large section of Mangrove forrest along pre-landfilled Shenzhen Bay, included extant Lychee orchards (and yes, students and teachers participated in early harvests) as well as planting garden areas and an artificial lake. According to SZU architectural student, from the outside the campus looked like waves of trees and low-lying buildings, while inside one could leisurely walk on shaded paths without the oppressive sense of skyscrapers or the disorientation caused by too many landmark buildings that stood apart from an integrated urban whole.

Participants agreed that early Shenzhen University reflected larger social goals to reform and open the Maoist system. They had been proud that SZU was not like Beida or Qinghua, they wanted to educated students who learned through doing, and they believed that universities had an important place in leading post Mao China. Indeed, they were not simply nostalgic for early SZU, but also and more profoundly, nostalgic for the Special Zone, when Shenzhen was a synonym with “experimentation” and “difference”, and “freedom” defined as a “return to [human] nature”. To this end, Teacher Liang made a point of quoting Liang Qichao’s Confucian motto for Qinghua University, “Strengthen the self without stopping, hold the world with virtue (自强不息,厚德载物)”.

Early SZU’s socialist /Daoist / neo-Confucian hybrid culture stands in marked contrast to the Municipality’s ongoing campaign to promote neo-Confucian harmony. The meeting ended with further comparisons to then and now; SZU, one of the participants maintained, had represented an architectural expression of educational values. Indeed, he lamented a fundamental change in attitude. Previously, SZU administration, teachers, and students had taken it as a point of pride that early reports criticized SZU as “not conforming to the standard (不和规矩)”. In contrast, today’s SZU was so busy trying to play catch-up that it had lost what made it special.

The comparison was explicit; just as SZU had become second-rate by relinquishing its experimental and creative mandate, so too had Shenzhen lost what once made it the epicenter of reform and opening a moribund system and thus a special zone.

This organizational meeting was part of the Shenzhen Design Center‘s (深圳市城市设计促进中心) series of public talks, Design & Life (设计与生活). The format begins with an architect led tour of an interesting Shenzhen building or site. This tour is open to the public, and then edited into a short film. The film is shown at a two-hour public talk, which includes a viewing of the short film and talks by three or four guests, concluding with a question and answer session.

The first two sites were the Nanshan Marriage Registration Hall (南山婚礼堂 by Urbanus) and the Shenzhen Music Hall (深圳音乐厅 by Irata Isozaki). Architect Meng Yan led the tour of the Registration Hall and Hu Qian, a Chinese architect who studied in Japan led the Music Hall Tour. The SZU talk will take place on August 25 at the Civic Center Book City.

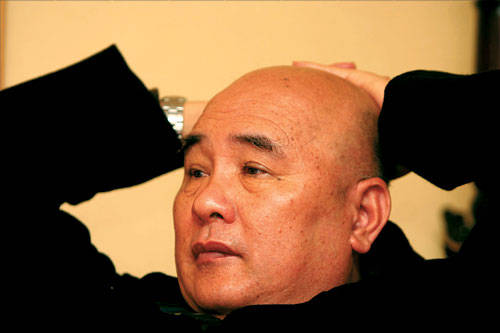

Luo Zhengqi will be the guest of honor.