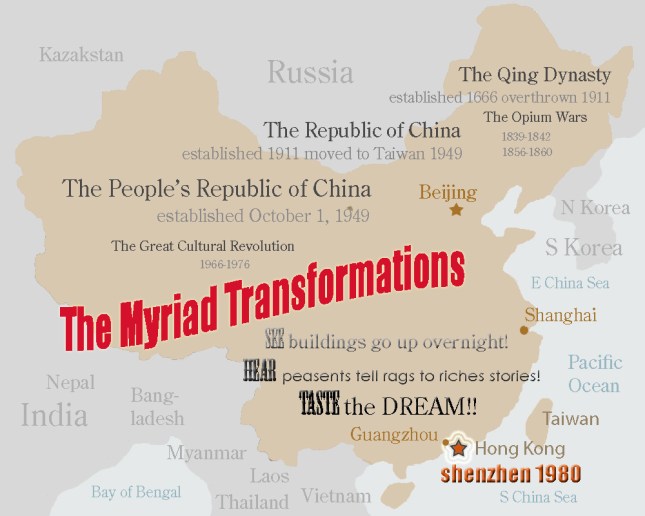

I have been used to thinking of the Cultural Revolution as the immediate backdrop to the ideological transformations initiated by the establishment of Shenzhen. However, as I was reacquainting myself with the cultural geography of Huaqiangbei I came across the Zhenhua Industries sign on Zhenxing Road. The logo is a throwback to Third Front industrialization, when futurist aesthetics still informed nationalist dreams. But what actually caught my eye was Jiang Zenmin’s calligraphy; by providing the calligraphy (题词) for this enterprise, the former General Secretary showed explicit support for the manufacturing company. After all, the most famous example of Jiang Zemin’s calligraphy in Shenzhen was written for Window of the World in 1994, as part of Overseas Chinese Town’s transition to leisure and tourism. So I was curious: when and how did he actively support Zhen Hua specifically and the construction of the Shangbu Industrial Zone more generally?

Third Front Industrialization

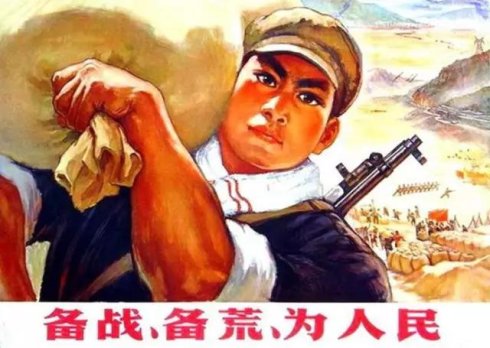

The story begins in 1962ish, when China’s leaders were debating the way forward after the disastrous Great Leap Forward. That year, Chinese leaders proposed that the country’s Third Five-Year Plan should focus on improving the standard of living, and was popularly known as the “food, clothing, and necessities plan (吃床用计划).” Mao Zedong opposed the plan, arguing that China’s Frontline cities were vulnerable to military attacks. He maintained that in order to defend against possible invasion, China should proactively move its manufacturing bases to its mountainous hinterland. At first, other leaders opposed the project, however, after the Gulf of Tonkin Incident, defense industrialization made sense to China’s other leaders. This initiative is known as the “Third Front construction (三线建设)” and it is the immediate background for the construction, development, and early fate of Shenzhen’s Huaqiangbei area. “Third Front,” of course, was a military reference to a “front line,” invoking the geography of China’s War Against Japan, when the country’s mountainous hinterland remained free from occupation.

Barry Naughton has pointed out that even if the Cultural Revolution decade (1965-1976) was marked by excessive politicalization and fragmented control, nevertheless the Third Front “was a purposive, large-scale, centrally-directed programme of development” that was more or less simultaneous with the Cultural Revolution. Indeed, the highs and lows of Third Front investment match the excesses and retreats of the CR. From 1965 through 1971, Third Front industries received the lion’s share of national investment in to further the development of defense, technology, electricity, iron and steel manufacturing, and other nationalized industries. When Zhou Enlai reclaimed control of the government apparatus in 1972, he modified the Third Front strategy to focus on completing key projects and to restore the economies of areas outside the Third Front region. Consequently, although investment in Third Front industries fell off from previous levels, nevertheless, from 1972 through 1978, these compounds continued to receive significant state subsidies.

Central to the spatial and social organization of China’s military industrial complex, Third Front compounds (院子) were a privileged form of work unit (单位). On the one hand, the perceived urgency of the simultaneous need to develop military capacity and to protect those installations from foreign armies produced a geography that “was located in mountains, scattered, and hidden in caves (靠山、分散、进洞).” These sites were not only locate in remote distances from each other, but also in remote distances from China’s older industrial centers. On the other hand, many of China’s technical personnel were employed by Third Front factories. They and their families moved from coastal cities to these compounds where they lived lives that were importantly isolated from surrounding communities. Consequently, even more than workers (工人) in China’s urban work units, “military workers (军工)” employed by Third Front factories relied on state subsidies in order to provide for their families.

Demilitarization of Industry

In 1979, before the SEZ was officially established, three minor Third Front enterprises from northern Guangdong were reorganized as “Hua Qiang” (literally, “Strong China”) Electronics Company. They were deployed / transferred to Shenzhen, where they began construction of the Shangbu Industrial Zone (上步工业区). Over the next few years, Third Front compounds would deploy workers and raise capital to invest in Shenzhen more generally and Shangbu, specifically. Zhen Hua or “Invigorate China” Electronics was one of the first Third Front companies to join Hua Qiang in the Shangbu Industrial Zone. Comprising over twenty companies from the Qiandongnan 083 base area (黔东南083), in Guizhou, Zhen Hua raised 10 million yuan to invest in the new SEZ. Nevertheless, the company needed support for the central government in order to expand its production from the safety of the Guizhou mountains to Shenzhen, which was not only located on the coastline (and therefore vulnerable to attack), but also had not yet received full support from central leaders.

The old brick infrastructure of the old factories are visible in this photograph of the gate for the newly established Zhen Hua Electronics Company. You can also see the aesthetic that still infuses the company’s Huaqiangbei compound (photo above).

Zhen Hua’s decision to invest in the SEZ more generally and Shangbu specifically was supported by reformers in the Central Government, who were pushing forward what was known as the “soldiers to people (军转民)” directive, decoupling military from civilian manufacturing. In the terms of the era, the goal was to provide the Chinese people with “a decent standard of living (小康)”–the same goals that had been shunted in favor of Third Front construction. These reformers included Jiang Zemin, who was appointed First Deputy Minister of Electronics in April 1982 and then Minister in June the following year. Jiang Zemin visited 083 several times, including in 1986, when as Minister of Electronics he approved the establishment of Zhen Hua and its decision to pursue civilian manufacturing at its window in Shenzhen. However, Zhen Hua was not formally designated one of the country’s 55 experimental enterprises until 1991, when Jiang Zemin provided the company with calligraphy that celebrated the restructuring of industrial manufacturing:

三线创业绩 振华开新天 The Third Front gets results, Zhen Hua starts a new day.

The signature on this celebratory couplet included the four characters, 中国振华 (China Zhen Hua) that still mark the entrance into its Huaqiangbei compound.

The decision to focus on electronics in the Shangbu industrial zone came from the central government. Moreover, the decision to focus on electronics offered many of the Third Front enterprises–and the government that continued to support them–a way out of the quagmire of failed industrialization. The story of how Zhen Hua’s decision to invest in Shangbu–and the way that they did–highlight the complexities behind Deng Xiaoping’s statement that “the center has no money, but we can give policies. After that, you’re on your own, cut open a road of blood (中央没有钱,可以给政策,你们自己去搞,杀出一条血路来).” Specifically, although the government could not fund new industries in Shenzhen, nevertheless, it allowed established industries to raise capital and transfer that investment from the interior to the SEZ. In addition to the Ministry of Electronics, the Ministry of Aviation also used Shangbu to restructure, separating military and civilian manufacturing, with civilian manufacturing located in Shenzhen.

The results of reorganizing manufacturing into military and civilian enterprises, Shenzhen not only provided a spatial fix caused by Third Front investment, but also justified bringing industry back to frontline cities. By the late 1980s, the state was offsetting the costs–social and economic–between subsidizing these compounds and closing them down in order to pursue more economically viable development. During the 1990s, of course, the state decided to “learn from Shenzhen,” gradually dismantling Third Front companies. Indeed, throughout the 1990s, representations of manufacturing in Shenzhen legitimated demilitarizing and degrading labor, which in turn created the highly gendered context of “path breaking” in the 1990s.