One of the highlights of the XLarch Masterplanning the Future Conference was Wang Yun (王昀)’s keynote speech that periodized the development of Chinese style architecture, arguing for an internationalist approach to architecture, rather than an ideologically charged use of architectural symbols.

As an architectural style, Chinese classicism was invented by western trained architects who upon returning to Nationalist China received commissions to build “Chinese style (中华风格)” buildings during the decade of 1927-1937. These buildings had large, Chinese style roofs, windows and decorative details, and sometimes included stylized gardens. The Nationalist capital, Nanjing was the location of some of the most important examples of this style as well because commissions not only represented individual client preferences, but also the determination of government leaders to create a recognizable Chinese public architecture.

One of the most important examples of Chinese classicism is the Nanjing Sun Yat-sen Memorial, which was designed by one of China’s first starchitects, Lv Yanzhi (吕彦直). Lv also also designed the Guangzhou Sun Yat-Sen Memorial before his untimely death in 1929. The Nanjing Memorial reinterprets traditional themes through choice of material (reinforced concrete and mosaic tiles) and through the secularization of traditional symbols (animals become geometric shapes, for example). In addition, the Memorial layout abstracts and represents Nationalist China as the difficult realization of Dr. Sun Yat-sen’s three principles of the people (三民主义) — nationalism, democracy, and public welfare. To reach the Memorial proper, for example, there are 392 steps going upward, each step representing one million Chinese, and together representing the population of nationalist China. These steps are broken by eight flat platforms, which represent the fragmentation of China by warlords and civil war. However, when one looks back on the stairs, all one sees is a flat surface, an optical illusion that promises national unification.

The Nanjing Sun Yat-Sen Memorial provides a lexicon for understanding Chinese Classicism during the Nationalist era, including the reference to the Lincoln Memorial (1920) by way of the seated figure of Dr. Sun (1926-29). Not unsurprisingly, perhaps, the Lincoln statue also dominates a neo-classical building, albeit through references to Greek architecture. Indeed, both the Sun Yat-sen and Lincoln Memorials use the respective classicism of their countries to assert timeless governance, even as they commemorate leaders who governed countries divided by civil war. I show the following images of the Nanjing Memorial with the caveat that they are not architectural — an architectural photo has amazing resolution, geometric composition, and absolutely no people, unless, of course, the figure contributes to architectural exegesis. My snaps, however, aim to emphasize just how popular this site is and thus how it continues to shape the visceral experience of being in “China” through a particular architectural style.

How does the Nanjing Memorial relate to Shenzhen?

This architectural lexicon has been picked up, tweaked and redeployed throughout Shenzhen, but as a private rather than public source of architectural symbols. The Luohu Train Station is the only exemplar of public Chinese Classicism that has been built in Shenzhen in the Reform Era. The other large example of post Reform classicism is the Hongfa Temple in Fairy Park, which is arguably political in its adamant denial of any political message. Certainly, in its assertion of the reintroduction of official religion to civic life, Fahong was as ideologically charged as the train station, which signaled China’s opening to capitalist countries. However, with the exception of these two buildings, Chinese Classicism in Shenzhen is limited to decoration in urban villages, where many handshakes have tiled roofs, restaurants, and the odd sculpture, such as Nvwa Holding up the Sky in Shekou, which is a socialist realist rendering of a mythic theme.

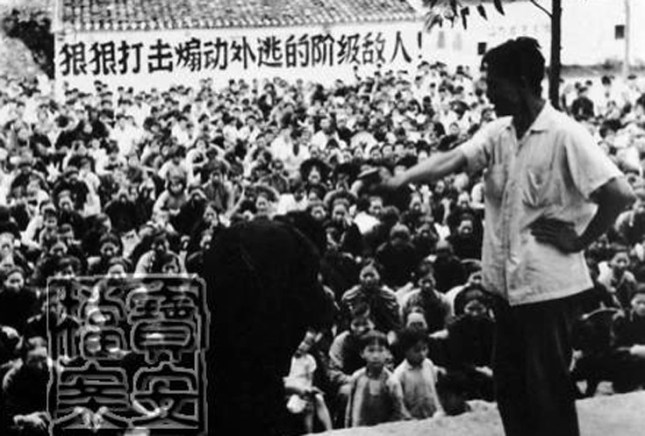

All this is interesting because given the explicit modernism of Shenzhen’s public architecture, the rediscovery or explicit use of Chinese tradition and roots are often used in neoliberal arguments for alternative forms of architecture and historic preservation. Chiwan comes to mind as do struggles for some form of preservation in urban villages. These efforts contextualize the design and construction of key civic architecture, including the Civic Center and central axis, which has the ideological expression of Reform and Opening (here, here, and here). Importantly, both the relentless modernization of Reform era public buildings and the alternative movement to construct a classical past for Shenzhen ignore Maoism, which nevertheless continues to inform the built environment.