shenzheners are developing an environmental consciousness. indeed, the shenzhen 2030 development strategy calls explicitly for sustainable development. so now we encounter billboards to protect endangered species. the irony, of course, is that these billboards have been raised at the former new houhai coastline. about 10 years ago, the elephant would have been standing on the beach. 20 years ago, said elephant would have been up to its knees in water, possibly even deeper.

save endangered species billboard

save endangered species billboardmoreover, only five years ago, if memory serves as well as i hope, the elephant would have been standing beneath “blue skies and white clouds.” these days, smog is an all too often topic of conversation in shenzhen. most folks blame the cars, and then quickly remark that cars are necessary, both for convenience and building the economy. all of us, however, lament that the environment has deteriorated so obviously, so quickly.

at the same time, shenzhen’s furious pursuit of garden cityhood proceeds. recently exotic plants abut the new roads and construction sites of the houhai land reclamation zone. although beautiful, these plants irritate me. unlike the once ubiquitous and local banyan tree, shenzhen’s palms and bushes and flowering trees don’t provide shade. they also require large teams of gardeners, who water the plants with an irrigation system that stretches along the ever changing coastline. these plants confound me. i wonder where their gardeners live and how much they earn; as far as i know, the blue uniformed gardeners in central park, live in dorms in the park itself, but there aren’t any dorms on the landfill, only temporary construction dorms. the extent of the irrigation system also has me wondering, given the city’s water shortage, who isn’t getting water if imported fonds are. and if perhaps, we’ve reached the final coastline.

this afternoon, on the landfill, i stopped to talk with several people. one, a migrant worker who had just came to shenzhen and lived in one of the nearby shanties, said that it was nice to walk on the coastline where the air was fresher. true enough. i actually breathed in salty air. a second interlocutor, was an old shenzhener, originally from ningbo, who like like me, enjoys photography. he showed me some of the pictures in his very nice camera–flowers, parrots, traditional architecture, and old village rivers.

“unfortunately,” he said, “shenzhen is a new city, so there isn’t much beauty here.” as i understood him, beauty referred to things natural and manmade that had a graceful harmony. he admitted that all shenzhen’s glass buildings were impressive, but not yet beautiful, unlike shanghai, where old sections of the city had been preserved and improved. his comments had me wondering if we wait long enough, shenzhen will become beautiful through age. although with all the upgrading and razing of older sections of the city, this path to beauty may not be the most efficient and shenzhen may as well just stick with its the newest is the most beautiful aesthetic. speculation aside, we agreed that the smog had become a serious problem that would become even more serious, “unless the government takes serious action.” as we separated, me to take more pictures of houhai and him to continue searching for beauty, he exhorted me to visit other cities, especially shanghai, “where the environment is really beautiful.”

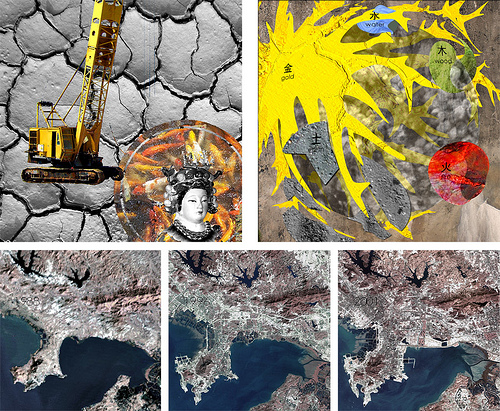

i am not sure if shenzhen’s utopian origin sets residents up for disappointment, or if memory creates beauty where it may not have been; i’ve been to shanghai, and i remember smog, in addition to the lovely buildings. i do think that the utopian impulse behind the city’s construction continues to inform longterm planning. the idea of shenzhen as a sustainable city is, if it is nothing else, a call to create a better future. and yet. houhai continues to transform the south china environment and climate at a pace unplanned, and more than likely, with unforeseeable environmental consequences.

pictures of plants and smog here.