Yesterday had a wonderful time with good friend Denise exploring Shatoujiao and then the land border from Wutongshan South to Liantang subway stations (Shekou Line). Three observations (with illustrations!) and unsubstantiated speculation, below:

First observation, a difference: Shenzhen has built up against the border; Hong Kong has not. In some cases, buildings form the border with windows looking south to Hong Kong. In contrast, Hong remains relatively uninhabited, while the Hong Kong Frontier Closed Area seems wild, broken up by infrastructure (as in the image above, which shows the Hong Kong and Shenzhen coasts of Shatoujiao Bay 沙头角海).

Second observation, a similarity: Both sides have a two-fence border system that has created a series of variously accessible frontier spaces. The two fence system creates a buffer zone between the city and the border, while between the two buffer zones is a third no-person area. From the Shenzhen side it is sometimes possible to see at least three fences–one between Shenzhen and the border area, one at the southern edge of the border area, and a third on the other side of the Shenzhen River. Denise tells me that the Hong Kong side (like the Shenzhen side) is also double bounded.

Third observation, an ethnographic note: yesterday was a Wednesday afternoon and older Hong Kong people were enjoying the coastal walking corridor in Shatoujiao, while Hong Kong Cantonese was the main language being spoken in Liantang Station as folks made their way to and from the border crossing. It seems Hong Kong retirees enjoy day-tripping.

Some speculation: the border itself is an apparatus of integration and maintaining it requires an incredible investment in land, energy, and human resources. Formally deployed as a site for assembly manufacturing and export logistics, it is now being restructured through consumer tourism.

On the one hand, the no-person zone manifests the idea of an “absolute separation” of the two cities. And yes, like most borders, it is an ironic separation given that the Shenzhen River forms a watershed that integrates the micro-ecology of the Shenzhen River Valley.

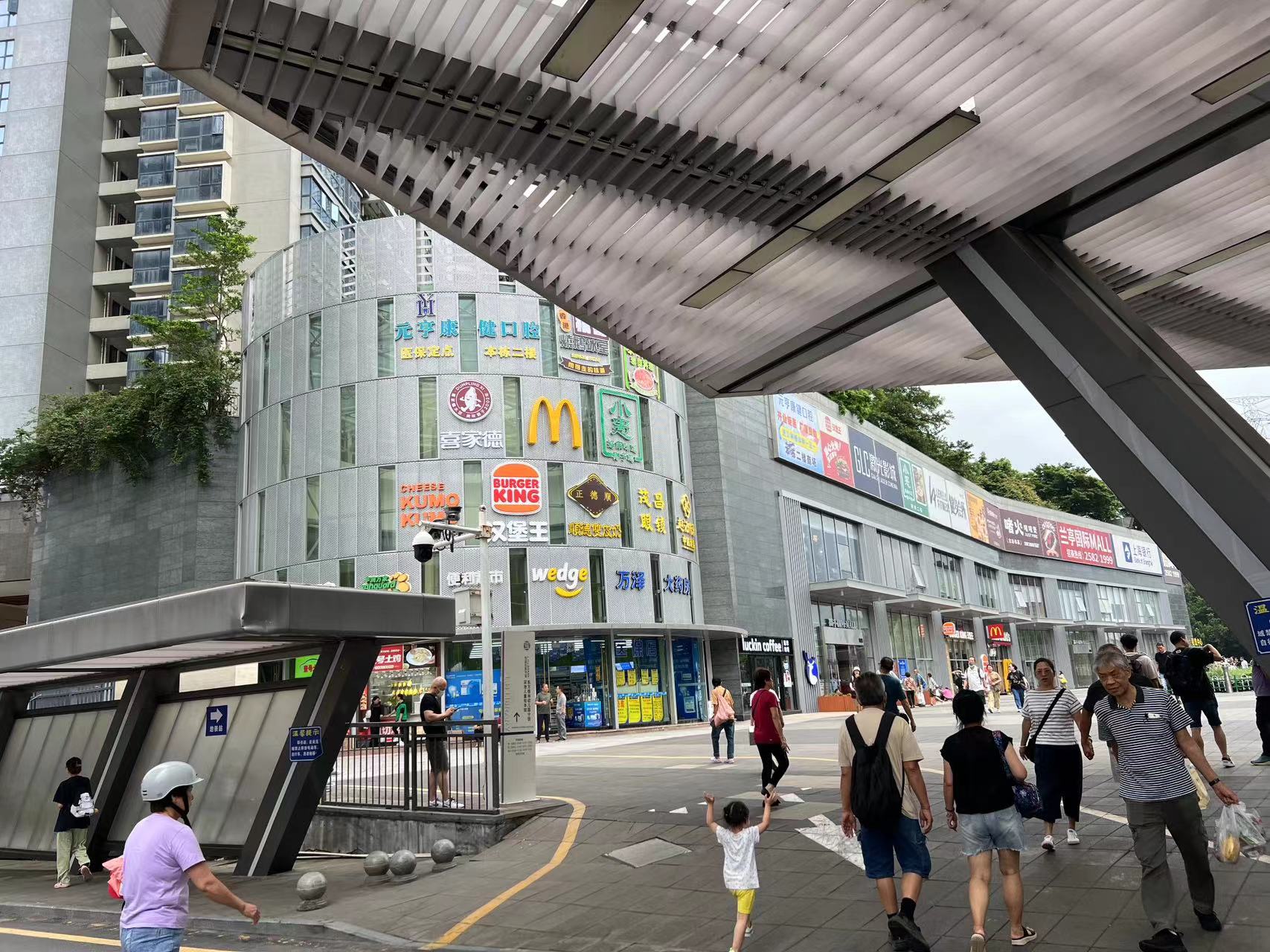

On the other hand, the buffer zones (formally called the Frontier Closed Area in Hong Kong) are patrolled and selectively inhabited. From the Shenzhen side, we saw that border residents kept gardens in their buffer zone. However, the Shenzhen buffer zone is being upgraded both through proposed parks and checkpoint malls, which streamline consumption in ways that Luohuo Commercial City did not. Beyond the “border tourism” organized at checkpoint malls, however, what is traditionally thought of as “border tourism” actually takes place along the outer fence.

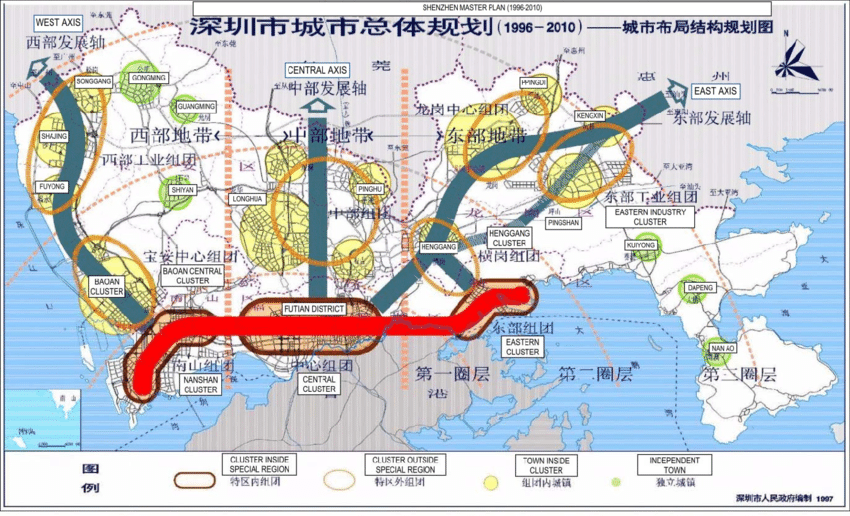

And in lieu of a conclusion: In Shenzhen, we can see how the Greater Bay Area is being formed. It is not “a mega city,” but an integrated region of connected, ranked urban nodes. The model for this new kind urban form is arguably the 1996 Shenzhen Comprehensive Plan, which organized the city into corridors and axes. Each of the axes radiated from the border, realizing the early Shenzhen policy of 外引内联, which can be loosely translated as “attract the foreign, connecting with the interior.” For more thoughts on the shifty shifting Shen Kong border, check out the essays in Transformation of Shen Kong Borderlands.